Location: Mifflin county near Poe Mills on Penn’s Creek (approximately: 40.82255,-77.40535)

Ben Kline’s books say that John Duncan logged both Swift Run and Rocky Run in the very early days of steam powered logging railroads, perhaps 1889 to 1899, well before he began his extensive operations at White Deer, PA. While traces of right of way do seem evident along Swift Run Road (aka Paddy Mountain Rd, aka Havice Valley Road), Rocky Run has always seemed impossibly steep and, er, rocky for a logging railroad.

Last week a group of us were out exploring in the general area and got to puzzling over Rocky Run on our way back out of the woods. Was it really ever accessed, or was Kline wrong? First, we examined the south side of SRR to the west of Rocky Run. Was there any way a route might have switchbacked off of Swift Run and wrapped around the end of Pitchpine Ridge to get higher up Rocky Run? The short answer: No.

We then decided to take another look at Rocky Run itself. We stopped at Point Lookout Camp and piled out. We gazed upon the small stream heading steeply uphill. We gazed at the big and jumbled rocks. We gazed at the slope. We muttered discouraged words and got back in the car!

Heading N/NE back towards Poe Mills, we studied the surrounding terrain, pondering how else Duncan’s men might have bypassed the lower portion of Rocky Run. We shortly realized that there are other gaps leading off Swift Run in the general direction of White Mountain and Rocky Run. One dead ends into White Mountain Kettle and thus seems a poor bet; a kettle is usually pretty snugly contained. The next gap to the south contains White Mountain Ridge Trail, which sounds much too developed. Probably a donut shop up there. But the gap to the SSW… hmmm.

We therefore parked along the road and attempted to cross Swift Run, made difficult by the fact that it’s fairly swift, not to mention wet and cold and wide. Spotting a small collection of hardware on display along the stream inspired us however, and we found a crossing and began exploring up the gap.

Only a few steps beyond the camp, I spotted some curious terrain that looked like it just could be grade. I decided it was worth proceeding, as the others fanned out in various directions. A short distance upstream I glanced up at a lengthy and well weathered timber running along my path and let out a whoop–two spikes were sticking out of it!

I gathered several others and we explored upstream. It seemed pretty likely there was track some distance, but due to the late hour and failing light, we decided to return another time.

The Second Visit, Leading to Other Surprises

On January 2 the weather was blustery but reasonable, so I called upon a team member to see if he was up to knocking out a survey of the new route. “Bring the metal detector!”, I urged.

Arriving at the unnamed stream, we started sweeping with the metal detector and quickly started pulling iron from the ground. Our first find was an interesting piece that looks like a hook off the end of a chain, perhaps part of a log car or even a horse’s trace chain. Typical early spikes (long and thin) were everywhere. We proceeded upgrade, confirming the route by finding traces of iron all over the place, including several places in the long timber mentioned above.

Eventually we reached a rather forbidding wall of earth where we had stopped on the earlier trip. It seemed impossible that they could have crossed it. Doing an “oh what the heck…” we climbed beyond it, only to find iron again immediately beyond. Turns out an earth slide in the intervening 120 years thoroughly buried the route, but it continues quite nicely! This is shown as ‘Earth Slide’ on the map.

Finally a rock pile did bring us to an abrupt halt. Above it was a strip of iron several feet long, with a chamfered end and regular screw holes; possibly a runner off a logging sled? It didn’t seem heavy enough or hammered enough to be strap iron for rail.

We continued a short distance uphill, theorizing that this region was perhaps used to skid logs to cars waiting just below. A nice signal from the detector set us to digging only to find… a horseshoe, complete with nails. Hmmm… Perhaps this region was used to skid logs to cars waiting just below!

Concluding that anything beyond really falls to HistoricHorsePoweredLogging.com, we headed back downhill, starting a GPS track at the upper reaches of what could have been track. The total survey was a hair under 1/2 mile, descending from 1515 feet at the horseshoe to about 1060 at the camp, giving an average 17% grade! Seriously.

But it Gets Better!

Returning to the car, we fortified ourselves with homemade apple pie and headed for Point Lookout Camp. One of those moments of: I know it’s impossible, I just want to see if it’s possible. With the GPS loaded with a track visible on aerial views, we started up a trail behind the camp. We know they didn’t go exactly this way, we gasped as we ascended the steep slope. After a bit it leveled off and we skirted the west face of a bulge of White Mountain.

Eventually it seemed we were coming into a leg of a hollow branching off Rocky Run. With some bare rock to the south, it seemed like a good place to do a transit of the hollow. Shortly after crossing a dry streambed, I glanced up and gave a start. What is this? My companion quickly came up and joined me in exploring a rock feature that was definitely constructed intentionally. We soon determined it couldn’t really be right of way. But it sure could be a large rock slide, in fact a funnel where several slides joined, thus I proclaimed it: Funnel.

Crashing about in the brush, we tried to determine where the logs went next after they were Funneled. It didn’t take long to realize a substantial trench extended north west. Perhaps they skidded the logs along here using horse power. The trench extended. And extended. After about 250 yards, we entered an area where rocks tumbled steeply down away from us to Rocky Run. The trench stayed to a gentle slope along the hillside. A good buzz from the detector set us digging only to turn up… a horseshoe! One could almost believe they skidded logs along here using horse power.

Finally the trench took a steeper dive down the hillside, and the metal detective hollered that we seemed to have a loading point. Perhaps if we looked below it we would find… iron? Of course, piles of it! But here we are, on the upper reaches of Rocky Run, where it is plainly impossible to be, yet we have iron. *sigh*

We made the decision to head upstream for a fixed time due to fading light, then survey downstream with the GPS, attempting to record the route out of The Impossible Rocky Run. Turning upstream, we looked in disbelief at where we were going. Is this possible?

Scouting ahead with the metal detector showed iron. We continued upstream, marveling at the rugged terrain and the tumbling stream that they somehow surmounted. The iron continued, and eventually we started finding scattered timbers containing traces of spikes.

After a bit it seemed we were through the worst of the gorge and it was obvious the sun was at the horizon. We decided we better head downstream, so we activated the GPS and retraced our steps. [Later study shows we were approximately 1200 feet downstream of Bear Gap Trail when we stopped]

With the detector to affirm our recollections, we returned to our starting point and continued beyond. Shortly after, the ground began to plummet and it seemed unimaginable to continue!

Yet the route is there, clinging to the south the east walls of the gorge. At one spot, we spotted a crude but unmistakable fill constructed of large rocks.

Right along here we encountered a fragment of splice bar, which suggests they had T rail here.

There is so little shelf along here that we figured they must have been substantially “cribbing up” one rail above the hillside. Sure enough, we eventually spotted flat rocks stacked together which must have supported the outside rail. It would take a braver engineer than me to run much along this stretch of track!

Eventually we came into the northerly stretch of the stream and it became apparent that we were headed directly for Point Lookout Camp. What had seemed an impossible grade from below was just another day at the office for Mr Duncan’s gents. From this angle it was possible to see a ledge through the Mountain Laurel leading right out to the empty concrete pond in from of the camp. Examining beyond, we could even find the route on the other side of the present day road. Where the road obviously cuts through a bank just adjacent to Pt Lookout Camp, the grade hugs the hillside closer to Swift Run. Following it along the road, it is rather obvious (now) where the switch for this line diverged from the main near the road bridge over Swift Run. Doh!

This track also ended up about 1/2 mile, descending from 1468 to 1255. That gives an 8% average grade, surprisingly “modest” compared to the other hollow.

Conclusions… and Questions

Looking back at the Kline books, it seems obvious and logical that much of Duncan’s operations out here were wildcat, i.e. gravity runs of log cars down the hills. How far up these grades they went with the empty cars pulled by the locomotive (an early Climax class A) is debatable; I have a hunch they went to the mouth of these particular gaps and not much beyond, leaving the poor draft horses to lug the empties up these grades into the woods and skid logs to them.

Although most of the spikes we found were long and narrow, we did find a T-rail style splice bar and some short and stubby spikes that suggest iron T rail. Also, the timbers we found with spikes in them are curious: the spikes occur in groups of two. That’s a style we’ve typically seen where we think they had iron rail spiked atop longitudinal logs. A wildcat road from 1889 would seemingly be using entirely wood (4×4 or 6×6) rails, or maybe wood with strap iron on top, but we can’t see how the hardware we found fits with that.

We did learn one big lesson today: Don’t doubt the determination of these people, even in the earliest days of operation. And second: For best results, carry a metal detector!

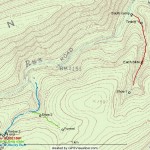

Here are maps showing what we found: